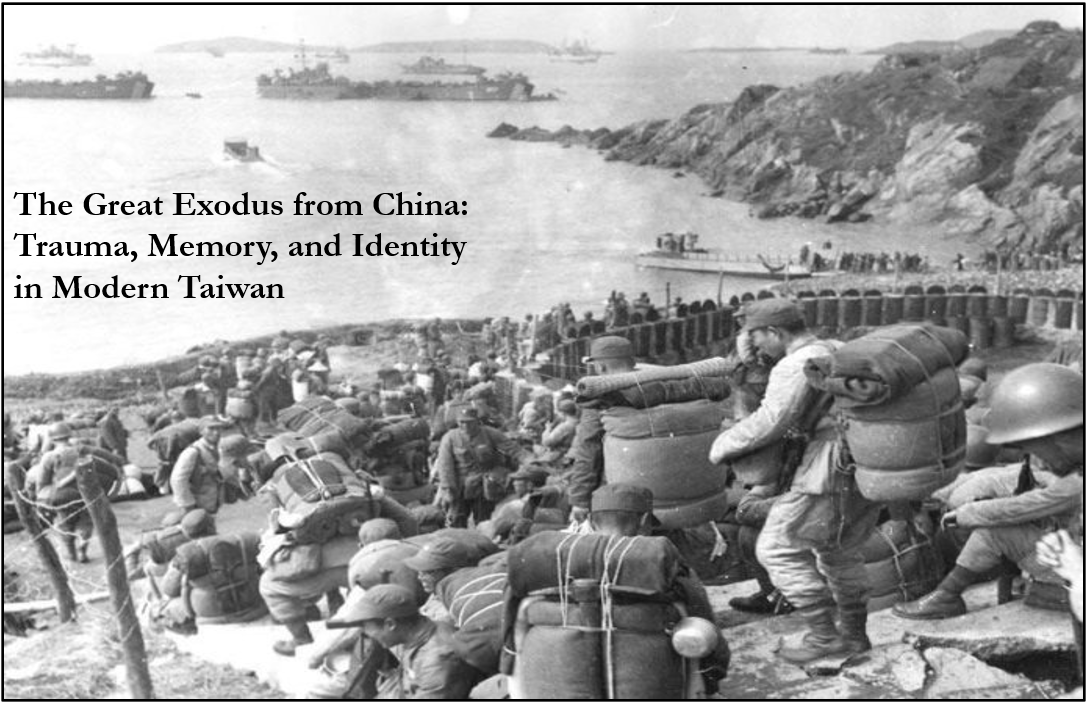

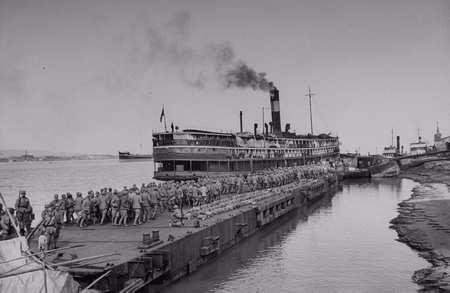

With the fall of Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist government in 1949, one of the largest involuntary migrations in Chinese history began. Whether terrified into fleeing by the prospect of communist rule or abducted outright by the retreating army of the Kuomintang, approximately one million people from all walks of life were displaced across the sea to the island of Taiwan. The consequences of this momentous event are still highly visible today, and Dominic Yang stands at the forefront of scholarly efforts to grapple with its fraught legacy. In his critically acclaimed first book The Great Exodus from China: Trauma, Memory, and Identity in Modern Taiwan, Yang’s groundbreaking research sheds light on the cataclysmic “retreat” of 1949 as experienced, interpreted, and remembered by those who lived through it. While the political, ideological, and military dimensions of the Chinese Civil War have long preoccupied historians, the human suffering and dislocation produced by the conflict remains largely unexplored and misconstrued. The Great Exodus from China lucidly demonstrates the processes through which ordinary refugees from the mainland and their Taiwan-born children came to terms with the ordeal of exile over time, from the initial moments of departure to their disappointing “homecomings” four decades later. The book is essential for grasping the enduring significance of this period, up to and including its influence on contemporary relations between Taiwan and China, above all with respect to their conflicting national identities and memory politics.

Dominic Meng-Hsuan Yang

For Yang, the allure of the topic is in part biographical. Having emigrated with his family from Taiwan to Canada when he was fourteen, his interest in the exodus crystallized upon returning to the island as a PhD student in the late 2000s. “After spending most of my formative years in North America,” he recalls, “I was struck by many interesting new developments in Taiwan, among them the tremendous number of published accounts, memoirs, even novels and TV shows focusing on the refugee experience of 1949. Interestingly, if you look back, there were no such stories being produced in Taiwan before the nation democratized in 1987. This got me intrigued.” As one might expect, the situation was quite different on the other side of the Taiwan Strait in the People’s Republic of China (PRC), where even today there is still very little written about the massive trauma and displacement inflicted by the civil war. As Yang explains, it is not all that difficult to understand why: “The Communists won what they called the ‘War of Liberation’ in 1949, so a brutal fratricide was interpreted as a grassroots ‘socialist revolution’ instead of an actual military conflict in which both sides committed atrocities. Today, the PRC remains a dictatorial state that does not tolerate deviations from the party line, whereas Taiwan has allowed its citizens to air long-suppressed personal narratives of the war.” This disparity runs throughout Yang’s analysis, though the internal divisions of Taiwanese society are just as relevant. Among the most significant revelations of The Great Exodus from China is that many exiles from the mainland had no concrete ties to the Nationalist regime at all, and some even opposed the dictatorship of Chiang Kai-shek. “The rest of the world has been under the impression that this was an anti-communist exodus,” Yang notes, “The reality on the ground was much more complicated. Hundreds of thousands of foot soldiers in Chiang’s army were draftees. Many were young peasants abducted by the Nationalist military at the end of the war. There were all sorts of refugees who had never worked for or been affiliated with the Kuomintang in China: doctors, dentists, barbers, grocers, etc.” Regardless of their backgrounds and beliefs, it is clear that the influx of people seriously disrupted existing conditions in Taiwan, where the island’s semi-Japanized “native” population was systematically oppressed by the new Nationalist government. Yang’s family belonged to this group. “Due to my upbringing, I used to have a highly negative view of the mainlanders, but that was because I knew very little about their history. I wanted to understand mainlander history. That’s how this project got started.”

Such an undertaking was fraught with methodological challenges inherent to the slippery nature of memory as historical evidence. After all, how can one trust the veracity of testimonies recorded long after the fact? What did elderly exiles from the mainland and their Taiwan-born children actually remember? Did they have ulterior motives for articulating their experiences publicly? If so, what were they? The situation is clouded further given that for decades the exodus was never even considered an important chapter in the history of the mainlanders, much less the central feature of a collective identity rooted in common suffering. Yang surmounts these difficulties by offering an innovative “multiple event” conception of cultural trauma and historical memory. He argues that “In order to understand why there is now an entire mnemonic enterprise built up around the history of the exodus, we need to understand that there were multiple instances of traumatization between 1949 and 1987, each of which evolved in accordance with the shifting circumstances of displacement. In short, people produced different memories at different times to come to terms with a series of heartbreaking changes.” This approach stands in marked contrast to how historians typically address issues of trauma and memory because it avoids the temptation to zero in on a single event or relatively short time frame (like September 11, for instance, or the Holocaust). By the same token, it also transcends the limitations of relying on a narrow scope. “Trauma is about repetitions in a struggle to accept a painful past. But repetitions, or ‘returns,’ as I call them, manifest themselves in a variety of ways, and they’re not always related to the initial event. That idea came out of Freudian psychoanalysis. It shouldn’t be taken as a norm for the rest of the world. Memory is selective, instrumentalist, and malleable. But it’s also therapeutic, emotional, and conditioned by a specific historical trajectory. It’s easy to say that all collective memories are ‘constructed.’ Okay, but in what ways? People choose to remember certain things at certain times based on the setting and the cultural repertoires at their disposal.”

That Yang’s book offers a timely and much-needed intervention is evidenced by the diverse sources of support he drew on in composing it. These include prestigious grants and fellowships from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) of Canada, the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange, the Republic of China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Institute for Historical Studies at the University of Texas. Equally indicative of its resonance is the substantial amount of academic recognition and public attention Yang’s work has garnered since the release of The Great Exodus from China in October 2020. It was recently selected to receive the annual First Book Award from the Memory Studies Association, and the author himself has been commended with the Provost’s Outstanding Junior Faculty Research and Creative Activity Award at the University of Missouri. He has also delivered no fewer than seven invited lectures over the past several months to audiences spread across three continents – from Seattle to Taipei to London. As Yang sees it, the popularity of the book stems largely from how it speaks to the universal phenomena of trauma, memory, and identity while connecting them to global concerns over refugees, displacement, and diaspora. At the same time, the positive reception of his work within the field of Asian Studies can also be attributed to its specific historiographical contribution: “The population movement that I study is one of the largest in the history of modern East Asia, but surprisingly little has been written about it, even though there are literally hundreds of books and articles about the Chinese Civil War, the Chinese Revolution, and the postwar history of Taiwan.” While scholars have examined the fate of mainland “escapees” to Hong Kong, moreover, they tend to concentrate solely on the implications of migration for the international dynamics of the Cold War. “These works generally don’t care too much about the lived experiences of refugees per se. In contrast, my book is all about the experiences of real human beings. It’s time we pay more attention to the human suffering produced by ideological conflicts and big power politics.”

Yang’s research footprint promises to grow yet further in the coming years as he prepares his second monograph, which will expand his earlier focus on these various threads to encompass the multifaceted relationship linking Taiwan with Hong Kong and the United States throughout the Cold War era. Here too, the relevance of his scholarship to contemporary affairs is unmistakable – all the more so in light of the PRC’s increasingly aggressive posture toward Taiwan and Hong Kong, not to mention the absence of a concerted response by the United States. “When I started this research a decade ago, China and Taiwan were on relatively good terms. There was even a naively optimistic belief that the two could finally ‘reunite’ peacefully, thus removing one of the most dangerous powder kegs in East Asia. I have always questioned this line of thinking, since my findings indicate that there are irreconcilable differences between China and Taiwan that become more and more apparent as people on each side get to know one another.” The same can be said with respect to Hong Kong, where regional fissures have only been deepened by “intimate contact” with the mainland and “indirect rule” from Beijing since the British withdrawal in 1997. “No-one wanted to deal with this back in the day. Everyone preferred to just kick the can down the road. Of course, it takes an ambitious Chinese leader like President Xi Jinping to turn the rolling can into a snowball that then morphs into an avalanche. Xi and his people know they have fundamental problems in Taiwan and Hong Kong, and that’s why they’re so determined to use force to ‘recover’ them before it’s too late. Here in the West, our policymakers just assumed that globalization, transnationalism, and capitalist modernity would solve every conflict in the world. Guess what? They haven’t.”

Yang has woven these sorts of insights into his approach in the classroom as well, where questions of historical memory serve a vital pedagogical function. “The training of historians is empirical first and foremost. We set out to do research in the archives in order to ‘rediscover’ a forgotten past that is useful for contemporary society to ponder over. This act is itself a form of memory production. The premise that there can be different interpretations of the same past is also roughly equivalent to how people have conflicting recollections of the same event. Each aspect can be an effective tool for imparting the techniques of history discipline.” By offering dynamic courses on the interrelated trajectories of modern China, Taiwan, and Japan, Dr. Yang has opened a window onto a part of the world that many students are intrigued by yet unfamiliar with. His class on Chinese migration to North America also enables them to apply the past to their own lived experience in the present through a framework that likewise breaks down cultural barriers. “We live in a world where sectarian conflict, political turmoil, and economic woes continue to drive displacement across national borders. Immigration policy is, of course, a hotly debated issue in the United States. By promoting the stories of refugees and migrants through my teaching, I want to get my students to reflect critically on their own biases as well as the potential costs of our misunderstandings. Of course, there are always going to be some who disagree with my viewpoint, and I think that’s quite healthy in a university classroom. But I can say with confidence that all of my students appreciate the opportunity to gain a wide range of perspectives on racism and immigration, and that’s the most important thing.”

**Your gifts to the department help sustain cutting edge research and teaching like this. To make a donation, please click here for the Give Direct page.