Chris Deutsch: Meat Regulation and Coronavirus

I am currently working on a book manuscript exploring the history of U.S. meat regulations and how the political battle over meat shaped larger battles over national economic prosperity. As a result, I have studied diseases spread by meat and how those threats have been managed. Current events have had me rethinking the nature of disease management and meat.

For a recent piece I wrote for Contingent Magazine, I shared my reflections on how the history of meat regulations illuminates an important aspect of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. The disease is tied to meat. The pandemic likely began in a Chinese market thanks to humans coming into contact with wild bats being sold for food. If the history of meat regulations within the United States has shown me anything, it is the need for regulating meat to prevent such occurrences.

Despite what it may seem like, the wild origins of the meat is not what matters here. Domestic food animals can cause deadly outbreaks. Recent examples include the 2009 swine flu pandemic and avian flu outbreaks in 1997 and 2004. These respiratory infections spread quickly and continue to haunt the meat industry. There are previous examples in U.S. history, though, of contagious diseases that have been eradicated and can help us understand the role of public policy in managing how meat is prepared and sold.

Diseases jumping from domestic meat animals to humans, called a zoonotic event, are common in U.S. history and zoonotic diseases have long been a danger of consuming meat. It is possible for meat regulations to make certain diseases rare. One of the most important zoonotic diseases made rare by changing regulations is trichinosis, a potentially deadly disease caused by trichinella roundworms living in uncooked or improperly prepared pork. For at least one-hundred years it was a scourge of the pork industries of Europe and the United States and pork consumers were constantly at risk from it. Particularly vulnerable were German consumers who favored raw pork dishes. Pig farmers, packinghouses, and consumers were helpless to dislodge the threat.

They were helpless, that is, until the federal government and state governments begin to address the problem through regulations. Spurred by an unrelated exposé of meatpacking abuse in Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, American consumers demanded that Congress finally take action on a meat inspection bill that had been sitting in a committee for lack of political will to advance it to a full vote. The result was the Meat Inspection Act of 1906. This unprecedented bill created the Meat Inspection Division and empowered the U.S. Department of Agriculture to use the most cutting edge scientific expertise available to fight diseases in meat and force the industry to clean itself up.

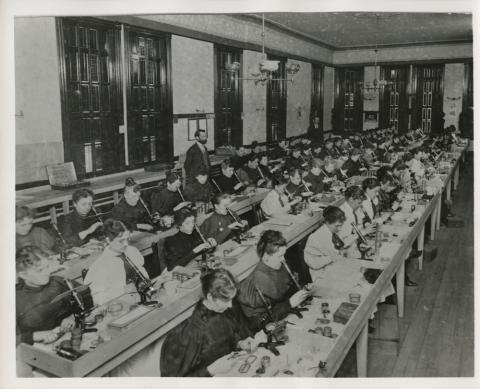

Empowered by vigorous popular support, the division set up labs and staffed them with women trained to look through microscopes for trichinella. However, despite their efforts, the meat inspectors and their workers made only a small dent in the prevalence of the disease. That is how things stood until the 1950s when a more aggressive set of policies were implemented. A different disease, the far deadlier virus vesicular exanthema, threatened the industry with collapse. Only then was the next step to defeat trichinella taken: new regulations requiring that the pork scraps fed to hogs had to be cooked, killing both. The two diseases have since become rarities.

As a result of both state and federal regulations, a zoonotic disease that haunted meat animals and meat eaters has become a rare threat. The disease is not eradicated and could return if the rules are ever relaxed. Other diseases await this kind of direct management. Regulations implemented in 1993 by Congress have allowed the Food Safety and Inspection Service, the successor of the Meat Inspection Division, to test for contagious diseases in meat animals but full eradication is lacking.

Zoonotic diseases spread when regulations are lax and enforcement weak. That is the one thing that studying the history of meat regulations has taught me. Coronavirus had its epizootic moment in a weak regulatory environment. Eating meat that others grow and prepare is a core part of our lives; yet it comes with it the requirement of vigorous vigilance and a constant need for regulatory oversight done in the name of protecting the people. While history cannot reveal the future, it can reveal deeper aspects of our present. Our health is entwined with the health of our food animals and we must never take that connection for granted.

Chris Deutsch is a Post-Doctoral Fellow in History at the University of Missouri. His forthcoming book, Beeftopia: The Beefsteak Politics of Prosperity in Post-war America, is currently under contract with University of Nebraska Press