The story I learned about society’s response to influenza in 1918-1919 mirrored each of these other pandemics. Some people respond to impending disaster by fleeing. Other people choose fight rather than flight, and they step outside their personal fears in order to help and serve. Some people respond to pandemics by panicking and hoarding food and supplies. Still others engage in denial, partying as the proverbial city around them burns. We certainly have seen all of these reactions in the pandemic we are now experiencing.

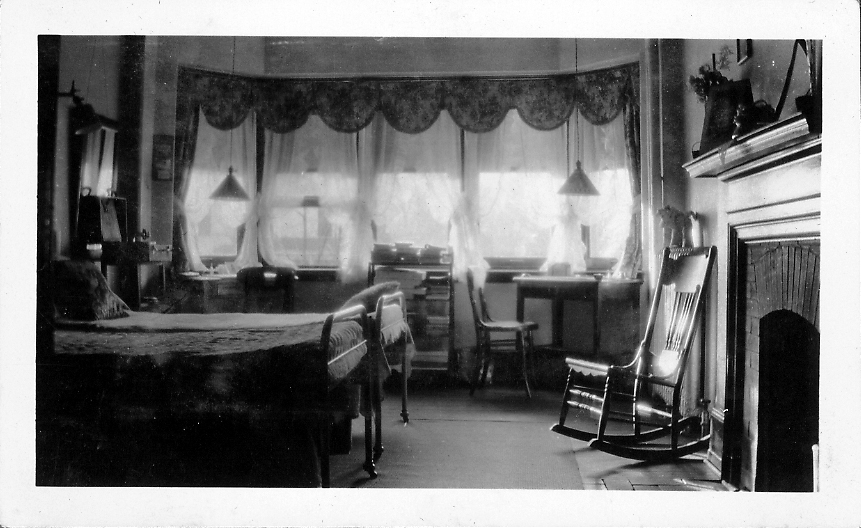

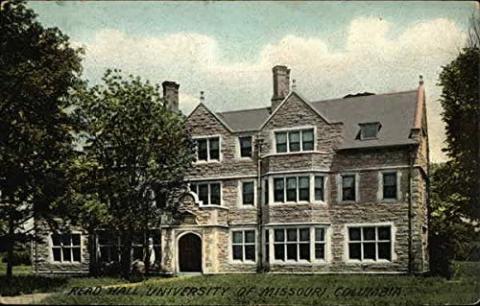

In September, 1918, newspapers in Columbia reported that the flu that was killing people in cities like New York and Philadelphia would soon arrive in the middle of Missouri. By the end of that month, Mizzou had responded to the coming crisis, restricting students’ activities and converting the women’s dormitory, Read Hall, to a hospital for women students. The Kappa Sigma house and one floor of Switzler Hall would provide “hospital” space for the University’s male students. Parker Hospital, which would later become University Hospital, served both male and female students. The Welch Military Academy (now Welch Hall), the Student Army Training Corps barracks on campus, and the Athens Hotel (at 817 E. Walnut) would serve as hospitals for the SATC students. In early October, Columbia’s Board of Health closed the K-12 schools and prohibited public gatherings, although Liberty Loan parades continued in support of American efforts in World War I. Despite the quarantine, people in Columbia and students at Mizzou began to fall ill. In the month of October alone, the University’s physicians treated more than 1,000 influenza patients, representing about 7% of the city and student population in the area. The University and the city repeatedly instituted, lifted, and reinstated quarantines throughout the fall and early winter, negotiating the demands of businesses that needed customers, students who chafed under long weeks of restriction, and working people who needed paychecks to survive. By the end of January, it seemed that the long months of illness and quarantine had passed, and life slowly returned to normal.

As I wrote my thesis, I often found myself wondering about the women who had filled the Read Hall rooms that were now my professors’ offices. Did those feverish, coughing students wonder whether they would ever recover? They did. After the epidemic passed, authorities reported that none of Mizzou’s women students had died of the flu. Will we ever return to the life we knew before we first learned of COVID-19? Mark Twain is reported to have said that history doesn’t repeat itself but often rhymes. Like the survivors of other pandemics, we will return not to the life that we once knew, but we will eventually be able to create a new normal.